A

Controlling the uncontrollable?

When I was asked to set up a new Lab for Printing and Publishing at the Van Eyck in Maastricht, I immediately realised that the Riso Duplicator would play an essential role in it. For many years, I worked, mostly with graphic designers, on publications printed in offset by a selected group of printers and bookbinders. Artists always felt uncomfortable to give main parts of the production out of their hands to external professionals, even though we always monitored the test runs.

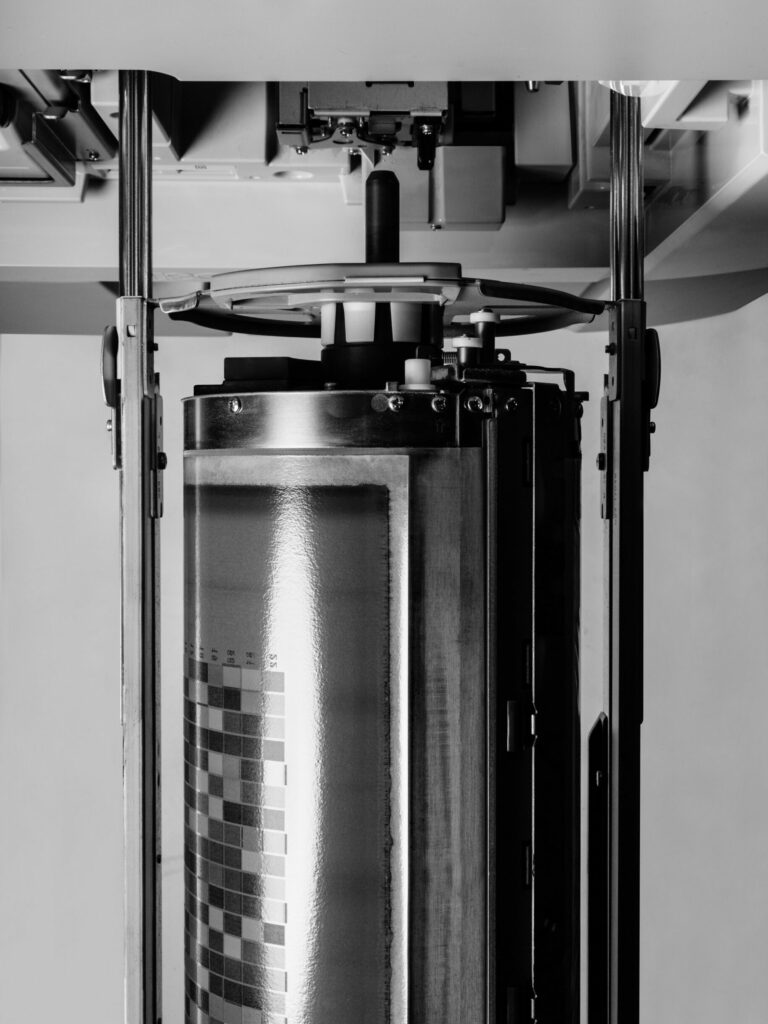

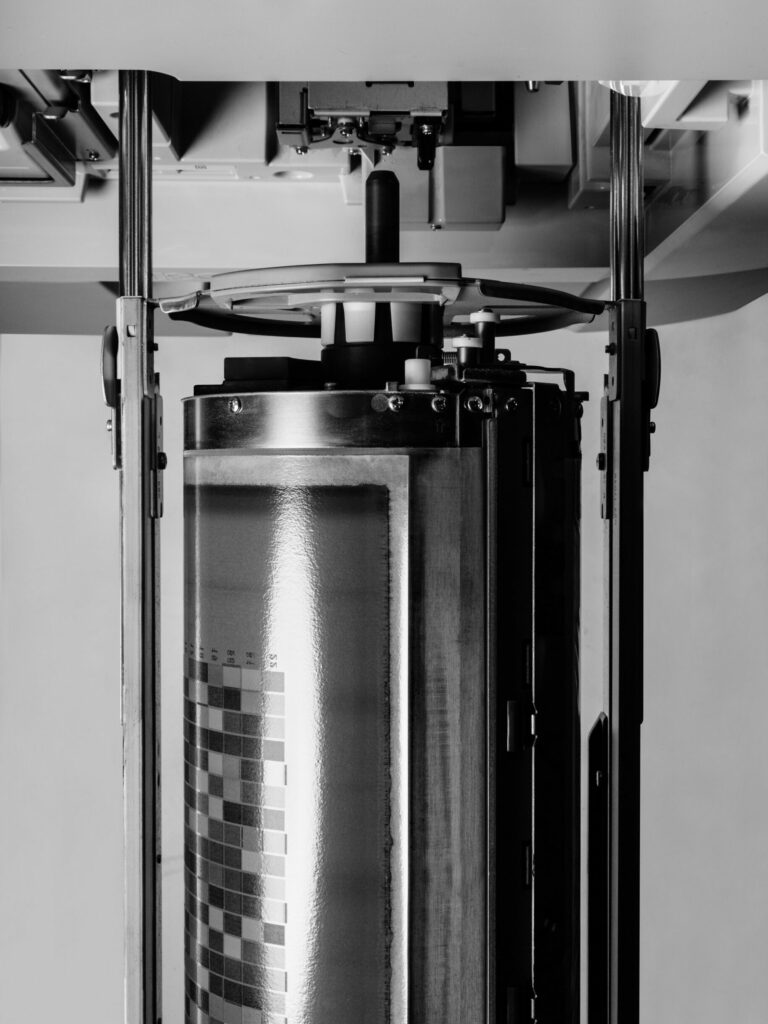

By giving the duplicator a central role in an environmentally friendly lab the artists could stay very close to the production process and make adjustments to their liking. Additionally, we offered peripheral equipment to be able to produce low edition artists’ books from A to Z. The Charles Nypels Lab was born and proved to be a success. Besides the argument of direct and low-cost accessibility to a press, the typical raw aesthetics of stencil printing with its vibrant colours are the most appealing characteristics embraced by a large and growing group of artists and designers.

After a long period in the offset world, the transition to stencil printing was a very liberating experience to me. Suddenly a lot of stress factors in production fell away, like subtle colour controls, resolution issues and registration on a micro-level. The focus was on content again.

Ironically, nowadays more and more appealing Riso colour charts and manuals are produced by colleagues who put a lot of effort into it. Mostly to communicate with their clients or out of pure joy, but also in trying to “control the uncontrollable”.

At the biennial Magical Riso conference organised by the Printing & Publishing Lab [then known as Charles Nypels Lab], a gathering of the main players in Risography, the request to Riso to start producing CMYK colours is a recurring topic. I truly hope that Riso will resist, it will degrade our beloved stencil technique to a “poor mans offset”.

Exploriso: Low-tech Fine Art by Sven Tillack is a courageous undertaking to write a new benchmark to Risography, with a focus on its technical aspects. I can imagine a publication like this will have regular updates in the future since fortunately, the stencil technique is more alive than ever. Many young colleagues are starting the adventure. I’m grateful to Spector Books that they provide the world with an English edition.

Jo Frenken

Head of the Jan van Eyck Academie Printing & Publishing Lab

Jan van Eyck Academie, Maasticht

The technology of aesthetics and the aesthetics of technology.

Risography as a walk across the aesthetic tightrope

A traditional, as well as widespread perception of art, is that art and technology contradict each other: Art defines itself by differentiating itself from technology, while technology is not art simply by virtue of being technology. In this concept, technology is seen as mechanical, dead and simply convenient, while art is seen as organic, alive and intrinsically logical. If you understand, however, that there is no art without technology, this distinction seems less plausible. Of course, it all depends on the question of what exactly is meant by technology. What is meant is not technology in terms of advancing the practical domination of nature, but of specific artistic procedures as well as artistic media. Artistic procedures refer to principles; those that constitute the artwork and those that help the artwork arrange its materials. This includes not only the individual use of the conventional subdivision of the tonal system into twelve semitones in the European music tradition in each musical work.

It is understood as a special process of reassembling sound by organising it in a certain way. On the contrary, it also includes a process such as that in Michael Hanekes Caché, in which the narrative uncertainty about the status of some cinematic images gives the whole movie an uncertain status. It is similar to a method like in Thomas Bernhardt’s Extinction: language is organised within the framework of an exaggerated narrative attitude so the topics dealt with are brought to a calculated as well as grotesque escalation. Artistic media, however, is to be understood as what is used in the production of the artwork and what makes that specific piece of art possible in the first place.

This obviously does not just include paper and pen, but also cameras and computers — as well as the process of risography. One characteristic of artistic media is that they turn into artistic media solely through use. Not everything produced with a pen is art. Not everything edited with a computer is art. And not everything produced with a risograph is art. Sven Tillack’s reflections on the history, technique, and aesthetics of risography also contain elements of what one might call the aesthetics of risography. It would not exist solely or primarily in the plane of the appearance of what was created using the process of risography.

It would rather comprise a special, aesthetic use of risography.

Sven Tillack’s reflections give some indication as to what that might entail. In the case of slight registration inaccuracies rendering the prints no longer “clean” and replaceable, risography offers special aesthetic options: the objects that were manufactured with it are now, in an aesthetic way, a reflection of their own manufacturing process. It is comparable, but not exactly identical, to using defective printers that leave artefacts on the prints or using devices that instantly fail in a calculated way. It should not just be about the technique of aesthetics, but also about technology being rendered aesthetic.

In the case of risography, this quite literally inscribes itself to the products and uncovers the peculiarity of their production.

As a whole, Sven Tillack’s book shows that risography, in its unclear status between being merely a technical procedure and a specific aesthetic, is an interesting subject for aesthetic practice as well as theory because its possibilities are far from having been explored to exhaustion.

Prof. Dr. Daniel Martin Feige

Professor of Philosophy and Aesthetics

in the Design Departement of the

Stuttgart State Academy of Art and Design

1

1

2

2

1

1

2

2